ARMS.

ARMS.

41.

THE

principal small arms used in warfare at the present day, are the common

or

smooth bore musket with percussion lock, the rifled musket, the rifle

with

elongated ball, rifled carbines, pistols and sabres.

42.

The

smooth bore musket (U. S. service pattern), is four feet ten inches in

length

from the butt to the muzzle; is provided with a bayonet eighteen inches

in

length, which fits upon the outside of the muzzle, and locks, so as to

prevent

its removal by an adversary; it has a bore of 0.69 of an inch in

diameter, and

carries a leaden ball running 32 to the pound. The musket with its

bayonet

weighs ten pounds nearly. The fire of the musket is inaccurate, but in

a

general action, where accuracy of fire is not attainable, it may be

made

effective up to 300 yards; beyond 400 yards it is useless.

This arm is being

rapidly superseded by

the rifled musket, or Mini~ musket, as it is sometimes called.

43.

The

rifled musket is nothing but the common musket “rifled;”

the grooves are three in number, they are of equal width,

and equal

in width to the

“lands;” the twist of the

grooves is a uniform spiral of one turn to six feet in length; the

grooves are

very shallow

MANUAL FOR VOLUNTEERS

AND MILITIA.

at the muzzle (0.005

of an inch), and

deepen slightly as they go down to the breech. The projectile, instead

of being

round, as in the common musket, is made cylindro-conical,

the cylindrical portion having three grooves around it, and

the base or

bottom being hollowed out in a conical form. Fig. 10 is a

representation of the

exterior of the ball, and Fig. 11 is a section through it showing the

shape of

the grooves, and the cone at the base. The object of giving the ball a

pointed

form, is that it may meet with the least possible resistance in its

flight

through the air; the effect of the grooves is, by the action of the air

upon

them, to keep the point of the ball in front, and cause it to strike

first; the

object of making it hollow at the base is, to make it expand when the

piece is

fired, thereby causing it to fill the grooves, and follow them in its

passage

out of the piece.

The dimensions of the

rifled musket (U. S.

pattern) are as follows: length, without bayonet, four feet

eight inches; with

bayonet fixed, six feet two inches; weight ten pounds;

diameter of bore 058 of

an inch; weight of ball 500 grains.

44.

The

“altered musket” of the U. S. service, is the old

pattern musket rifled; the

principal difference between this and the new rifled musket being, that

the

altered musket has a larger bore, its diameter being 069 of an inch.

The ball

carried by it is heavier, weighing 730 grains, and a heavier charge of

powder

is necessary.

45.

The

rifle, or Minie rifle, as it is

generally called, is rifled in the same manner as the muskets; the

diameter of

the bore is 058 of an inch, the same as the new musket, and the same

ball is

used; it is shorter than the musket, being but four feet one inch in

length,

without the bayonet, and not quite six feet with the bayonet fixed; its

weight

is greater than that of the musket, it being, without the bayonet, ten

pounds,

within a small fraction, and thirteen with it. The bayonet is not quite

twenty-two inches in length; it is made in the form of a heavy sabre,

but slightly

curved near the point. It is usually worn at the side, and is only

fixed when

pressed by cavalry, or in a charge.

46.

There

are several forms of rifles and carbines which are

ARMS.

More or less in use

by mounted troops, as

Colt’s repeating carbines and repeating rifles,

Maynard’s, Burnside’s, and

Sharp’s rifles, and Sharp’s carbine, all of which

are breech-loading arms. Colt’s

rifles are intended for both round

and elongated balls; in the others, the elongated ball alone is used.

47.

The

pistols in general use at this time are the largest size of

Colt’s repeaters;

they are rifled, and may be used as carbines by the attachment of an

“adjustable breech.”

There is also a

“pistol carbine”

manufactured by the U. S. ordnance department; it is rifled,

has the same bore

as the rifle and rifle musket, and the same ball may be used, although

a ball

with a larger cavity than that of the rifle ball is preferable. This

arm may be

used as a pistol or carbine — in

the latter case an adjustable breech becomes necessary.

48.

All

cavalry and artillery troops are armed with sabres, the U. S. cavalry

and

artillery sabres have steel scabbards, are forty-three and thirty-eight

inches

long respectively, and arc attached to “sling”

belts, which are worn around the

waist.

49.

The

fire-arms used in artillery are divided into three classes, guns, howitzers, and mortars.

Guns are used to throw solid

shot, which cut by their force of percussion, hence they are always

fired with

large charges of powder, say from one-fifth to one-half the weight of

the ball.

They are used to strike an object direct,

and at a distance; or by their ricochet

fire for reaching objects not attainable by direct

fire. They are also

used to batter down the walls of fortifications. They are always

designated by

the weight of solid shot which they carry.

There are six

different calibres, which

are divided into three classes, according to the position in which they

are to

be used; they are 6, 12, 18, 24, 32, and 42-pounders.

50.

The

6 and 12-pounders, usually made of bronze, but sometimes of

cast iron,

constitute one class called field guns; the

12, 18, and 24-pounders, made of cast iron, constitute a second known

as siege and garrison guns; and

the 32 and 42-pounders,

also cast iron, make the third, denominated sea-coast

guns.

Field

guns are used in the field as light

artillery; siege and gar-

MANUAL FOR VOLUNTEERS

AND MILITIA.

ARMS.

MANUAL FOR VOLUNTEERS

AND MILITIA.

ARMS.

rison guns are used

in permanent and field

fortifications, and in sieges, to batter down the

walls, etc; sea-coast

guns are principally used in permanent fortifications, on the sea board.

51.

A

howitzer is a gun with a chamber in it. It is used

principally

for firing hollow projectiles, or shells; in order to prevent breaking

the

shell, and at the same time to give the projectile sufficient

velocity, a

small charge of powder is fired from a cylindrical chamber at the

bottom of the

base.

The calibre of

howitzers is designated by

the weight of the solid shot which they would carry, or by the number

of inches

that the bore is in diameter. They are divided into field

howitzers, mountain howitzers, siege and garrison,

and sea-coast howitzers; field

howitzers are 12, 24, and 32-pounders;

mountain howitzers are 12-pounders, siege and garrison howitzers are

24-pounders and 8-inch, and sea-coast howitzers are 8 and 10-inch.

52.

Field

howitzers are used with light batteries ill the field; the mountain

howitzer is

for service in countries too rough to admit the passage of wheeled

carriages;

siege and garrison howitzers are used in the trenches at sieges, and in

the

defence of permanent fortifications; and sea-coast howitzers

are used in permanent

fortifications on the sea-board.

53.

There

are several kinds of mortars ranging from six to sixteen

inches in calibre;

the heavy mortars are principally used on the sea-coast; the others are

for use

in the trenches at sieges, and in the defence of fortifications of all

kinds.

54.

Pieces

of artillery are mounted on their carriages by means of trunnions;

they are cylinders east with the gun, having a common

axis perpendicular to that of the gun. The trunnions of the 6-pounder

gun, and

12-pounder howitzer have the same diameter, so that guns and howitzers

may be

mounted on the same sized carriages, and serve together in the

same battery;

the trunnions of the 12-pounder gun, and 24 and 32-pounder howitzer,

are also

of the same size, so that they may be thrown together in the same

battery.

Fig. 12 gives the form of the 6-pounder gun, with the names of the

parts, and Fig. 13 represents

a 12 and 24-pounder

howitzer

55.

The field gun carriage is composed of two parts; the

portion on

MANUAL FOR VOLUNTEERS

AND MILITIA.

Which the piece rests

when it is fired,

and the limber.

The first part,

or carriage proper, is two wheeled; from the axle proceeds the stock,

tp

which are fastened two upright pieces called cheeks,

upon

which the trunnions rest. The end of the stock designated the trail, rests on the ground during the

firings; at other times it is attached to the limber; the piece gets

its proper

elevation by means of the elevating

screw, which works through a plate on the stock. Fig. 14

represents the

gun and carriage with the names of the parts, one wheel being removed

to show

them the better. The limber is the part of the carriage to which the

horses are

attached; on the end of the trail is an iron plate called the lunette, through which there is an

opening,

which goes over a book on the axle of the limber called the pintle-hook, and is secured in its place

by a bolt called the pintle-bolt. The

limber also carries an ammunition-box, which may be removed at pleasure.

56. Each piece is

followed by its caisson or carriage, for ammunition.

The wheels of the carriage, limber and caisson , are all of the same

size; and may, when

necessary, replace each other, and a spare wheel is carried on the rear

of

every caisson. The caisson carries three ammunition boxes, of the same

size as

the one on the limber, and movable, so that when the box on the limber

is

empty, it may be exchanged for a full one from the caisson. The boxes

are

partitioned off into small compartments, each compartment being the

receptacle

for a charge of ammunition.

Every artillery

carriage is drawn by from

four to six horses, a driver being required for each pair of horses.

_____________

AMMUNITION.

57.

When

troops are in the field it is not only necessary that they should go

with a

sufficient supply of ammunition, but that it should be put up in such

form as

to be convenient for use, and at the same time as well protected as

possible

from the effects of the weather, etc. Cartridges made of paper or

flannel, or

some other woollen

AMMUNITION.

goods are in general use; the former for small arms, the latter for artillery.

|

|

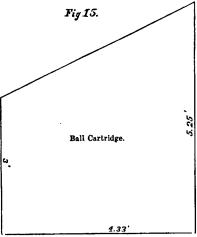

58.

To make the cylinders for blank cartridges, the paper is

cut in the form

represented in Fig. 15, with a

pattern. The former is a cylinder

of

hard wood of the same diameter as the ball, concave at one

end, and convex at

the other. The paper is laid on a table with the side perpendicular to

the

bases next the workman, the broad end to the left, the former

laid on it with

the concave end half an inch from the broad edge of the paper, and

enveloped

in it once. The right hand is then laid flat on the former, and all the

paper rolled on it.

The projecting end of

the paper is now neatly folded down into the concavity of the former,

pasted,

and pressed on a ball imbedded in the table for the purpose.

Instead of being

pasted, these cylinders

may be closed by choking with a string tied to the table, and having at

the

other end a stick by which to hold it. ‘Ihe convex end of the

former is placed

to the left, and after the paper is rolled on, the former is taken in

the left

hand, and a turn made around it with the choking string half an inch

from the

end of the paper. Whilst the string is drawn tight with the right hand

the

former is held in the left with the forefinger resting on the end of

the

cylinder, folding it neatly down upon the end of the former. The choke

is then

firmly tied with twine.

59.

For

ball cartridges, the cylinders are made and choked as above, and the

choke tied

without cutting the twine. The former

MANUAL FOR VOLUNTEERS

AND MILITIA.

is then withdrawn,

the ball inserted, and

followed by the concave end of the former. Two half-hitches are made

just above

the ball, and the twine cut off.

For ball and

buck-shot cartridges make the

cylinder as before, insert three buck-shot; fasten them with a

half-hitch, and

insert and secure the ball as before.

For buck-shot

cartridges make the cylinder

as before, insert four tiers of three buck-shot each, as at first,

making a

half-hitch between the tiers, and ending with a double hitch.

60.

To

fill the cartridges, the cylinders are placed upright in a box, and the

charge

poured into each from a conical charger of the appropriate size; the

mouths of

the cylinders are now folded down on the powder by two rectangular

folds, and

the cartridges bundled in packages of ten. For this a folding-box is

necessary;

it is made with but two vertical sides, at a distance from each other

equal to

five diameters of the ball, and two diameters high.

Put a wrapper in the

folding-box, and

place in it two tiers of five cartridges each, parallel to each other

and to

the short sides of the wrapper, the balls alternating; wrap the

cartridges

whilst in the folding-box, by folding the paper over them, and tie

them. A

package of twelve percussion caps is

placed in each bundle of ten cartridges.

The bundles are

marked with the number and

kind of cartridge.

61.

The

cartridges for elongated projectiles differ so much from those used

with the

spherical bullet, that a separate description is necessary.

Each cartridge is

made of three pieces of

paper, the larger piece or cartridge proper, (see Fig. 16, No. 1,) is

made of

what is known as cartridge paper, but it should not be too strong; the

second

piece, No. 2, is made of the same

or

stronger paper, and the third, No. 3, is made of the stoutest rocket

paper.

Before enveloping the

balls in the

cartridges, their cylindrical parts should be covered with a melted

composition

of one part beeswax, and three parts tallow; it should be

applied hot, in which

ease the superfluous part would run off. Care should be taken to remove

all the

grease from the bottom of the ball, lest by coming in contact

AMMUNITION.

with

the bottom of the case it penetrate the paper, and injure the powder.

62. The sticks on

which the cartridges are

rolled are made of the same diameter as the bore of the piece; the

dimensions

given

are for the U. S.

musket or rifle of O-58

bore. The piece of stiff paper No. 3, is laid upon No. 2, as shown in

the

dotted line of the figure; the stick is laid down on the side a,

b, c, the end being at b,

and the

paper rolled around it; the projecting end is then folded down and

pasted.

After the cylinder thus made is dry, it is again put on the stick; the

stick is

then taken in the left hand and laid upon the outer wrapper, the end

not far

from the middle of the wrapper, (the oblique edge of the wrapper turned

from

the workman, the longer vertical edge towards his left hand,)

and snugly

MANUAL FOR VOLUNTEERS

AND MILITIA.

rolled up. The ball

is then inserted in

the open end of the cartridge, the base resting on the cylinder ease,

the paper

neatly choked around the point of the ball and fastened by tying with

cartridge

thread. The stick is then withdrawn, sixty grains of powder poured into

the

case, and the mouth of the cartridge is “pinched”

or folded in the usual way.

The cartridge is shown in Fig. 17.

63.

To

use this cartridge, tear the fold and pour out the powder; then seize

the ball

end firmly between the thumb and forefinger of the right hand, and

strike the

cylinder a smart blow across the muzzle of the piece; this breaks the

cartridge

and exposes the bottom of the ball; a slight pressure of the thumb and

forefinger forces the ball into the bore clear of all cartridge paper.

In

striking the cartridge the cylinder should be held square across, or at

right

angles to the muzzle; otherwise, a blow given in an oblique

direction would

only bend the cartridge without breaking it.

64.

The

ammunition for artillery consists of a charge of powder contained in a

cartridge-bag, and the projectile, which may be either fixed to, or

separate

from the cartridge. When the two are fastened together, the whole

constitutes a

charge of fixed ammunition.

65.

The

cartridge-bag should be made of merino, bombazette, or flannel, which

should be

all wool, otherwise fire might be left in the piece after its

discharge. The

texture and sewing should be close enough to prevent the powder sifting

through. Untwilled stuff is preferable. The bag is formed of two

pieces, a

rectangle, which forms the cylinder, and a circular piece which forms

the

bottom. As the stuff does not stretch in the direction of its length,

the long

side of the rectangle should be taken in that direction, otherwise the

cartridge might become too large for convenient use with its piece. The

material is laid sometimes several folds thick, on a tablet and the

rectangles

and circles marked out on it with chalk, using, for the purpose,

patterns made

of hard, well-seasoned wood, sheet iron, or tin. The pieces are then

cut with

the scissors. For a 6-pounder gun and 12-pounder howitzer, the

rectangle is

11.4 inches long by 7.25 inches in height, the diameter of the bottom

being

4.37 inches—the seam is half an inch wide. For the 12-pounder

gun, and 24 and

32-pounder howitzer, the rectangle is 14.2 inches

AMMUNITION.

MANUAL FOR VOLUNTEERS

AND MILITIA.

AMMUNITION.

by 10,

and the diameter of the bottom is 5.25 inches,

The short sides of the rectangle are sewed together, and

the bottom

sewed in. The sewing is done with woollen yarn, twelve stitches to the

inch.

The two edges of the seam arc turned down on the same side, and basted,

to

prevent the powder from sifting through.

Blank cartridge-bags,

or those intended for immediate use,

may be made of two rectangular pieces with semi-circular ends sewed

together.

66. When special accuracy is required, charges are carefully weighed in delicate scales; but usually the bags are filled by measurement. The powder measures are made of sheet copper; they are cylindrical, and their diameters and height are equal. A measure 3.628 inches in diameter and height, holds one and a quarter pounds of powder, the charge for a 6-pounder gun when it fires solid shot; one of 3.368 inches holds one pound of powder, the charge for the same gun when it fires spherical case or canister; it is also the charge for the 12-pounder howitzer. A measure of 4.24 inches in diameter and height, holds two pounds of powder, the light charge for a 24-pounder howitzer; one of 4.57 inches holds two and a half pounds of powder, the heaviest charge for the 24-pounder howitzer, and the light charge for the 32-pounder. The one pound ~nd a quarter measure, and the two pound measure, making three and a quarter pounds, will be the heavy charge for the 32-pounder howitzer.

67.

Blank cartridges,

and those for the 12-pounder gun, are, after being filled, simply tied

firmly

about the neck with twine. Those for fixed ammunition are attached to

pieces of

wood called sabots,

by tying

them with strong twine, before attaching them to the sabots,

however, the sabot must be fastened in the projectile.

The sabot (Fig. 18), for guns, is cylindrical, or nearly so, in shape, and for howitzers, conical. For shot and spherical case for guns, they have one groove for attaching the cartridge; those for gun canisters, and for 12-pounder howitzer shells, spherical case, and canister, have two grooves. Sabots for 32-pounder and 24-pounder howitzers have no grooves, but are furnished with han-

MANUAL FOR VOLUNTEERS

AND MILITIA.

dles

made of a piece of cord, passing through two holes, and fastened by

knots

countersunk on the inside.

68.

The sabots are

fastened to shot and shell with strips of sheet tin. For shot there are

two

straps crossing at right angles (Fig. 19), one passing through a slit

in the

middle of the other. For shells there are four straps soldered to a

ring of

tin; the straps are nailed to the sabot. If tin cannot be procured,

straps may

be made of strong canvass, one

inch

wide, sewed at the point of crossing. The part of the ball which is to

be

inserted into the socket is dipped in glue; the straps are glued to the

ball,

and nailed to the sabot.

69.

A canister shot is a

cylinder of tin, of

the same diameter as the bore of the piece, filled with small balls.

(See Fig.

20.) The cylinder is left open at both ends; after being soldered, it

is nailed

|

|

to the sabot, and a

plate of rolled iron placed at the bottom

of the sabot. To prevent rusting, the cylinder before filling

should be

covered with beeswax dissolved in spirits of turpentine, and the balls

should

be painted or lacquered.

To fill the canister

place it upright on

its sabot; put in a tier of balls, filling the interstices

with dry sawdust,

packing it with a pointed stick, so that the balls will hold by

themselves when

the case is turned over, and throw out the loose sawdust. Place another

tier of

balls, and proceed in the same manner until the canister is filled;

cover the

top tier with a layer of sawdust, and put on the cover, which is a

circular

plate of sheet iron, settling it well with a mallet in order to

compress the

sawdust.

The top of the cylinder is cut into slits about half an inch lon which

are

turned down over the cover to secure it.

70.

The shot, shell, or

canister being secured to the sabot, the cartridge is tied to it,

making the

charge complete. The mouths of the bag are first twisted and pressed

down, so

as to settle the powder; they are then opened and the powder smoothed.

The

AMMUNITION.

sabot

is introduced, and the cartridge drawn up around it, until it reaches

the

powder; the cartridge is then secured by passing several turns of

strong twine

around it in the grooves, and tying it, after which the excess of the

bag is

cut off. (See Fig. 21.)

71.

The

cartridge and projectile for the 24 and 32-pounder howitzers

are kept

separate; the projectile is attached to the sabot as has been

|

shown (see No. 68,

and Fig. 19), and the cartridge to a cylindrical piece of light wood

called a cartridge block.

(Fig. 22.) These blocks give a

better finish to the cartridge, help to fill the chamber, and keep the

cartridge from turning in the bore while the piece |

|

is being loaded. They have but one groove; the grooved end is inserted in the mouth of the cartridge, and pressed down upon the powder; the bag is pulled over it and tied with twine in the groove. The mouth of the bag is then turned down, and another tie made over it, which keeps the powder from working up between the block and the bag. The superfluous part of the bag is then cut off.

MANUAL FOR VOLUNTEERS

AND MILITIA.

72.

For the greater

security of field ammunition, the cartridges are covered with paper

cylinders

and caps. They are both made together, on the same former, which is a

piece of

board with slightly inclined sides, and rounded edges. The paper is

pasted

around this. The requisite length for the cylinder is cut from the

smaller end,

the rest forming the cap, which is choked at the end from which the

cylinder is

cut. For choking, a cylindrical former of wood, with a hemispherical

end, is

used, which should be bored through the end to facilitate the drawing

off of

the cap. The cylinder fits over the body of the cartridge and a part of

the

sabot to which it is tied, while the cap fits over the end. When the

cap is

drawn off, which is always done when the cartridge is placed in the

piece, the

lower end is left exposed so that the priming wire, or fire from the

friction

tube, can reach it without going through any paper.

73.

Shells are hollow

shot, the interior space being formed of a sphere concentric with the

outer

surface, making the sides of equal thickness. They have a conical

opening or eye, used to load the

shell, and in

which is inserted the fuze to

communicate fire to the charge.

74.

To load shells,

they are set upon their sabots, the charges measured out in the proper

powder

measure, and poured in through a copper funnel. The 32-pounder requires

a

charge of one pound of powder (rifle or musket powder) to burst it, the

24-pounder twelve ounces, and the 12-pounder seven ounces. If now the

shell is

to be fired by an ordinary fuze, (see article on fuzes,) a conical

piece of dry

beech is firmly driven into the eye, and then a hole is reamed out

through it

to receive the fuze, and stopped with a wad of tow, the fuze not to be

driven

in until the shell is to be fired.

75.

Spherical case, or Schrapnel shot, as they are called,

after the English officer who

brought them to perfection, are thin-sided shells in which, besides the

bursting charge, are placed a number of musket balls. Their sides are

much

thinner than those of the ordinary shell, in order that they may

contain a

greater number of bullets; and these acting as a support to the sides

of the

shell prevent it from being broken by the force of the discharge. The

weight of

the empty case is about one-half that of the solid shot

AMMUNITION.

of the

same diameter. Lead

being much more

dense than iron, the schrapnell is, when loaded, nearly as heavy as the

solid

shot of the same caliber; but on account of the less charge which it is

necessary to use to prevent breaking the case, their fire is neither so

accurate nor the range so great as with the solid shot. But when the

schrapnell

bursts just in front of an object the effect is terrible, being as

great as the

discharge of grape from a piece at a very short range.

76.

To load a

schrapnell shot, the requisite number of balls are placed in; the shell

for a

6-pound gun requires thirty-eight balls, that for the 12-pound gun and

howitzer

seventy-eight, the 24-pound howitzer one hundred and seventy-five, and

the

32-pound howitzer two hundred and twenty-five. The balls being

inserted, a

stick a little less in diameter than the fuze-hole, and having a groove

on each

side of it, is inserted and pushed to the bottom of the

chamber by working the

balls aside. The shell is then heated to about the melting point of

sulphur,

and melted sulphur is poured in to fill up the interstices between the

balls.

When the shell is cool the stick is withdrawn, and any adhering sulphur

is

removed.

If a fuze-plug and

common fuze are to be used, the charge is

placed in and the plug inserted as for shells; but if the ]3oarmann

fuze is to

be used, (see the article on fuzes,) the charge is to be inserted, and

the

stopper and fuze are screwed into their places. The bursting charges

are as

follows: for the 6-pounder, 2~5 ounces; for the 12-pounder, 45 ounces;

for the

24-pounder, 6 ounces; and for the 32-pounder, 8 ounces.

77.

A fuse is a

contrivance for

communicating fire to the charge in a shell. It consists of a highly

inflammable composition, inclosed in a wood, metal, or paper case. The paper fuze consists of a

conical paper

case, containing the composition, whose rate of burning is shown by the

color

of the case, as follows:

Black burns

two seconds to the inch.

Red

“

three

“

“

“

Green

“

four

“

“

“

Yellow

“

five

“

“

“

Each fuze is made two

inches long, and the

yellow burns, cons-

MANUAL FOR VOLUNTEERS

AND MILITIA.

quently, ten seconds. For any shorted time, the fuse is cut with a sharp knife. This fuse is not placed in the sh~dl until it is to be fired, when the wad of tow is removed from the fuze-plug, and the fuze pressed down with the thumb.

78.

The Belgian or Boarmann fuze is the best now in use.

The fuze case is made of

metal (an alloy of lead and tin), and consists, first (Fig. 23), of a

short

cylinder, having at one end a horse-shoe shaped indentation, one end only of which communicates with

the magazine of the fuze placed in the centre. The indentation extends

nearly

to the other end of the cylinder, a thin layer of metal only

intervening. This

is graduated on the outside into equal parts, representing seconds and

quarter

seconds, as represented in Fig. 24. In the bottom of this channel a

smooth

layer of the composition is placed, with a piece of wick or yarn

underneath it;

on this is placed the piece of metal represented in Fig. 25, the cross

section

of it being wedge-shaped; and this is by machinery pressed down upon

the

composition. The cylindrical opening represented at a, Fig. 23, is

filled with

fine powder, and covered with a sheet of tin, which is soldered in its

place,

closing the magazine from the external air. Before using the fuse,

several

holes are punched through this sheet of tin, to allow the flame to

escape into

the shell. On the side of the fuse the thread of a screw is cut which

fits into

one on the inside of the fuze hole, and the fuze is screwed into the

shell with

a wrench.

79.

The thin layer of

metal over the composition is cut away with a gouge or chisel of any

kind, at

the point marked with the number of seconds which we wish the fuze to

burn. The

metal of this fuze being soft, there is danger of its being driven into

the

shell by the explosive force of the charge. To prevent this, a circular

piece

of iron, of a less diameter than the fuze, with a hole through its

centre, and

the thread of a screw on the outside, is screwed into the fuze-hole

before the

fuze is placed in.

The regularity and

certainty of this fuze is very great; one

of its most important advantages is, the fact that the shells can he

loaded,

all ready for use, and remain so for any length of time, perfectly safe

from

explosion; as the fuze can be screwed to its

AMMUNITION.

MANUAL FOR VOLUNTEERS

AND MILITIA.

place,

and the composition never exposed to external fire until the metal is

cut

through. The only operation to be performed when the shell is to be

fired, is

to gouge through the metal at the proper

point,

which may be done with any kind of a chisel, knife, or other instrument.

80.

Fire is communicated

to the charge in a cannon by means of priming

tubes and friction tubes.

Quill

priming tubes are

made from quills by

cutting off the barrel at both ends, and splitting down the large end

for about

half an inch, into seven or any other odd number of parts; these are

bent outwards,

perpendicular to the body of the quill, and from the cup of the tube.

Fine

woollen yarn is then woven into these slits, like basket work, the end

being

brought down and tied on the stem; or a perforated dish of paper is

pasted on

them.

These tubes are

filled by injecting into them, with a tube-injector,

a liquid paste made of

mealed powder and spirits of wine; a better method is, not to make the

paste

too thin, and then press it in with the thumb. A strand of quick match,

two

inches long, is now laid across the cup, and pasted in them with the

powder

paste. A small wire is then run through the tube, and remains there

until the

paste is dry; this leaves an aperture, furnishing a quick communication

for the

fire along the tube. A paper cap is placed over the cup, and twisted

tightly around

the tube under the cup.

Fig. 20

|

|

Tubes are also

made of metal, they are

either moulded, or formed into tubes by machinery. They are filled,

primed, and

capped, in the same way as quill tubes.

Priming tubes are now

almost entirely superseded

by friction tubes, which are made

by

machinery at one of the U. S. arsenals.

To fire priming tubes

portfires are used; they consist

of paper cases, filled with a highly inflammable, but slowly burning

compo-

AMMUNITION.

sition,

the flame of which is very intense and penetrating, and cannot be

extinguished

with water.

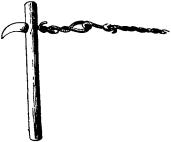

Friction tubes are fired by means of a lanyard; this is a stout cord which has a wooden handle at one end, and an iron hook upon the other; the cannoneer puts the hook through the loop in the wire of the friction tube (Fig. 26), and holding the lanyard by the handle, pulls steadily until the wire is withdrawn, when an explosion takes place, induced by the friction of the wire against the composition in the tube.

For more complete information on 19th Century Military Drill, visit the main page.